As I sat down to write this blog, I saw a tweet from superstar Carli Lloyd announcing that, with less than a week before the U.S. Women’s National Team match against Portugal on August 29th, 44,100 tickets had been sold, breaking the USWNT attendance record for a stand-alone friendly. I was so excited upon hearing this news, not just because they are so deserving of the recognition they’ve received, but because breaking this record would allow young girls and aspiring soccer players a chance to see themselves reflected in this sport. (In the end, the match drew a record crowd of 49,504!)

My background in STEM, culturally responsive pedagogy, and research methods has given me the opportunity to work with everyone from teachers and school administrators to police officers on the importance of cultural proficiency and promoting equity through their lens. I am a scientist at heart, but I’ve always had a love for the sport of soccer.

As a black girl growing up in Miami, I never saw soccer as a sport for me because it had always been a predominately male sport. I remember watching soccer with my daddy and simultaneously screaming “GOAAAAALLLL” until our lungs collapsed. You see, my family is from Haiti and soccer (better known as foutbòl to Haitians) is the most popular sport in Haiti. But even with it being the most-watched sport in my household, I never thought that I could be a soccer player. Maybe if I was a little girl and turned on the television to find Carli’s excitement, maybe then, I would have seen myself reflected as a female in a male-dominated sport, and just maybe I would have felt included.

So when I was asked by the U.S. Soccer Foundation to be a guest speaker at the their Soccer for Success National Training this summer, I jumped at the opportunity. The four-day event brought together coach-mentors from across the country who spent the long-weekend learning and engraining themselves in the new curriculum so that they, in turn, can return home to train their community members on how to deliver the Soccer for Success program to local youth. In addition to teaching soccer fundamentals (being coaches), these individuals are also trained to teach children critical life skills (they are also mentors), earning them the title of a coach-mentor.

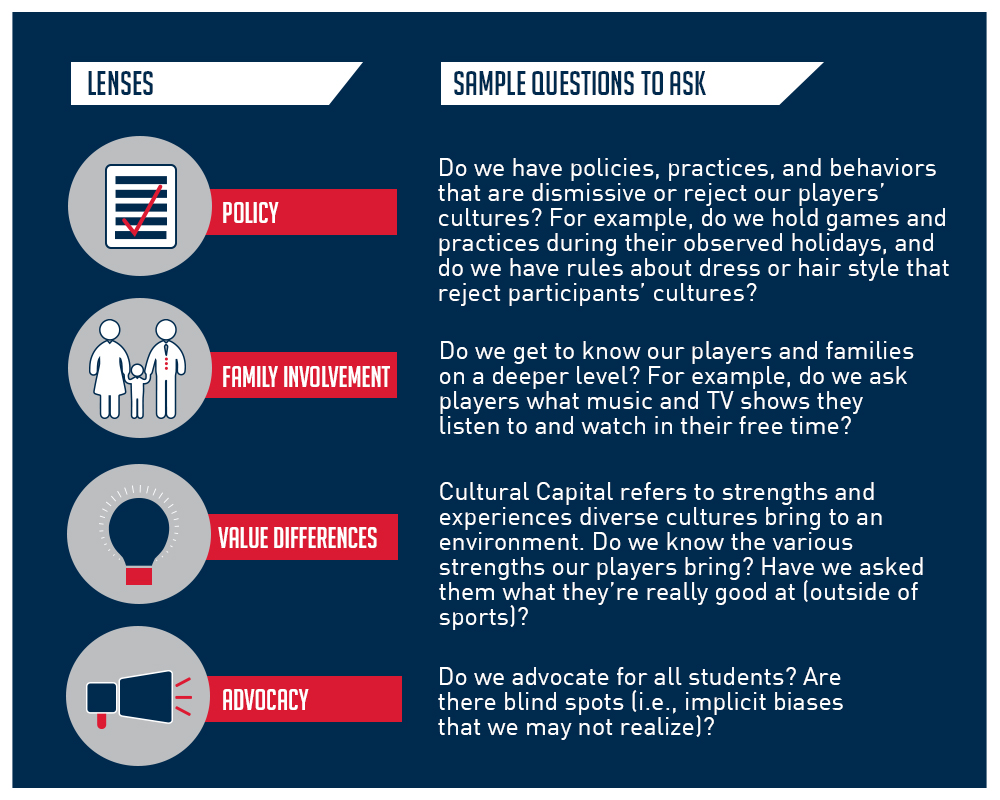

It’s my belief that, in order to be a good coach-mentor, you have to understand the youth you serve. With this in mind, my presentation focused on culturally responsive practices that create inclusive communities. My goals were to share strategies to help youth development professionals establish safe spaces for their youth by building both knowledge of themselves and others, and to unpack cultural competence. The ultimate goal was to create an environment where we could have rich conversations about increasing opportunities for youth to see themselves in this sport.

So what role does cultural competency play in the lives of coach-mentors?

The first thing we addressed during my presentation was respecting and honoring our unique cultures. Culture encompasses a variety of factors, such as race, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, spirituality, disability, the list goes on. Simply put, culture is how we do things around here. There are aspects of culture that are surface-level and are external and/or observable processes – like language or dress.

Then there are deeper, immaterial parts of culture that we cannot see. To truly understand youth and those vast communities we serve, it is imperative to move past surface culture and unpack beliefs, values, and thought patterns. Eye contact is a perfect example of deep-level culture. In my Haitian culture, direct eye contact with elders is traditionally considered rude; yet, growing up in American culture, my teachers would constantly request that I make eye contact when speaking or being spoken to. I quickly learned that what I thought was a sign of respect was not “the way we do things around here!”

In your community, you will meet youth from various cultures. Some aspects of their cultures are easily observable, but there are others such as personal space, preference for competition or cooperation, and definition of obscenity that will not be observable. In order to establish meaningful relationships, you must move past a surface-level understanding of your community and the youth you serve.

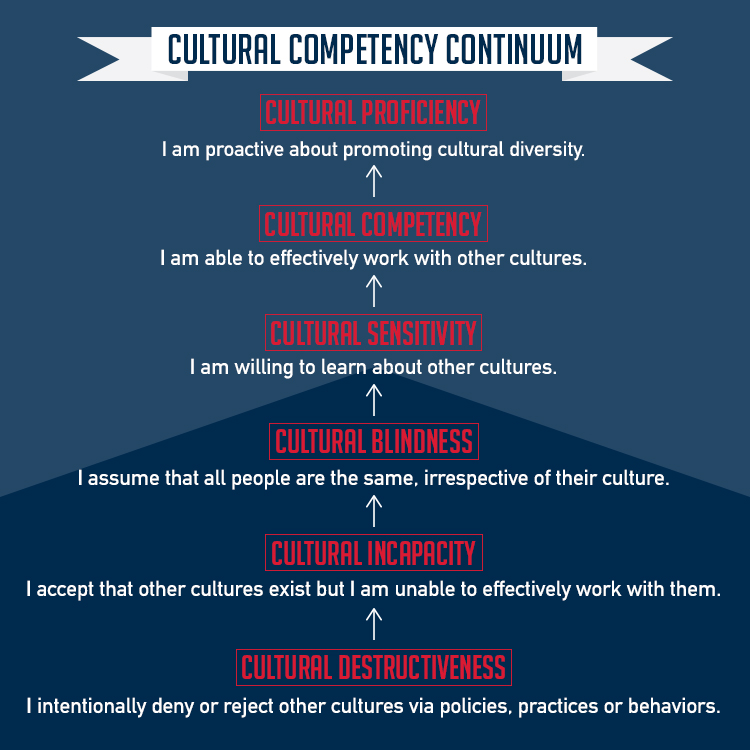

Additionally, you must move towards being culturally proficient. During the session, we spoke about the Cultural Competency Continuum. At the bottom of the continuum are values and behaviors that do NOT enable people and organizations to interact effectively in culturally diverse environments (i.e., cultural destructiveness and cultural incapacity). In the middle is cultural blindness and it is least discernable but has damaging effects. An example of this is “I don’t care if my players are pink, brown, or polka dot. I don’t see color. I treat all my players the same.” Well, coach, if you don’t notice you have a polka dot player on your team, you’re either color-blind or you’re missing an opportunity to bring their polka dot experience onto the field.

Next, you move to cultural sensitivity (where you recognize and are willing to learn about differences) and then to cultural competency (where you can effectively work in cross-cultural environments). Last is cultural proficiency, where you see differences and respond proactively, affirmingly, and you’re seeking opportunities to improve cultural relationships.

Adapted from Lindsey R., Robins, K. N., & Terrell, R. (2009). Cultural Proficiency: A Manual for School Leaders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Adapted from Lindsey R., Robins, K. N., & Terrell, R. (2009). Cultural Proficiency: A Manual for School Leaders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Moving from Theory to Practice

I can’t change the past, but together we can change the future for today’s youth. We can ensure that more children from underrepresented populations see themselves reflected in this field. Even if they don’t aspire to be professional soccer players, being exposed to soccer teaches our youth lifelong lessons such as discipline, leadership, resilience, collaboration, and sportsmanship – lessons every young person can use.

I like to use these tips & tricks to help me along the way:

The work that we do is critical for social change. Collectively, coach-mentors have the ability to work with children who don’t know that soccer can be a life-changer. By honoring, affirming, and respecting our cultural differences, we model what young people need to see in order to do the same – but to do that, we must go first.

The work that we do is critical for social change. Collectively, coach-mentors have the ability to work with children who don’t know that soccer can be a life-changer. By honoring, affirming, and respecting our cultural differences, we model what young people need to see in order to do the same – but to do that, we must go first.

Dr. Patricia Morgan is the Science, Health, and P.E. Coordinator for Fayette County Schools and completed her dissertation on the role of race in the classroom at Georgia State University. In addition to this work, she employs her expertise as an equity, diversity & inclusion consultant. In her free time, she enjoys binge-watching Netflix series and traveling. She is on a mission to see 50 countries and 50 states by 2022.