Let soccer do what soccer does.

Together, we can give millions of kids from underserved communities safe places to grow, thrive and build confidence for life.

A Soccer for Success Innovation

You could say that Vanessa Spero’s decision to host a summer Soccer for Success program for children with Down syndrome was a personal one. Having seen the great work that her colleagues do to run Soccer for Success through UF/ IFAS Extension Osceola County 4-H, she saw how the program positively engaged children in sport. As a mother to a six-year-old son with Down syndrome, Vanessa saw an opportunity. “I look at things in youth education and opportunities that are presented to [my son] and his peers so I really wanted to do a little bit better in 4-H,” she says. “We are completely inclusive, but we don’t really tell people that.”

But that’s not the only reason this summer program was close to her heart. Vanessa, Regional Specialized 4-H Agent II in the South District, is also completing her graduate studies for an educational doctorate, specializing in exceptional student education. “I made it my summer project while rolling everything together for grad school, for work, for personal and professional interest,” she says.

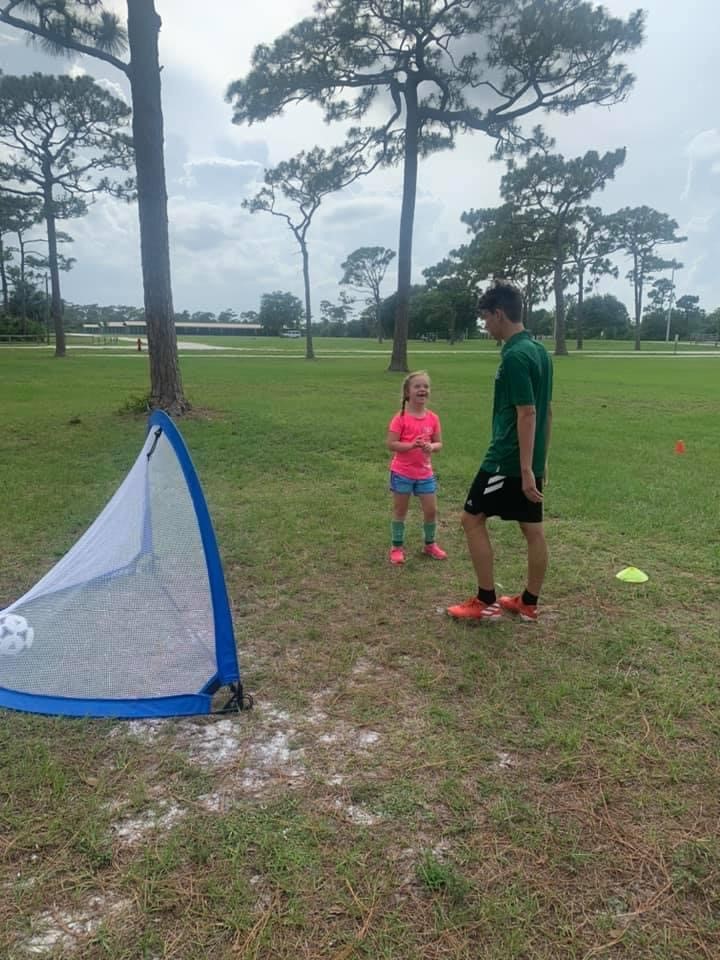

Through the Teens as Teachers program at 4-H, Vanessa worked to train local teens to help run a summer Soccer for Success season for children with Down syndrome. “We had about six kids that signed on to be teens as teachers this summer,” recalls Vanessa. “We also offered them two different opportunities – one of them was soccer – and just about everybody participated in soccer at least once. We did a training with them on youth development and being a teen teacher, and I did a small snapshot on kids with disabilities and Down syndrome and what to expect.”

The program was open to the Down syndrome community for elementary school-aged kids. The hope was to expose the teens to kids with disabilities and hopefully broaden their perspectives and experiences if they had never been around someone with a disability.

While the group initially hoped to mimic the Soccer for Success curriculum as much as possible, the teens and program operators found that they had to deviate a bit to keep the kids engaged. “The majority of what we were doing was focusing on skills and trying to get the kids to engage as a team a bit more, play with each other,” says Vanessa. “As a group, they didn’t really interact. Everybody wanted to do their own thing. We weren’t there to make it a miserable experience, and we weren’t going to be like ‘No, everybody has to do this now,’ because that wasn’t the point. The point was to be adaptable.”

One teen teacher, Haleema, took a unique approach to coaching. “One of the most challenging aspects of coaching the program was trying to keep up and earning the children’s trust. Of course, we had been coached ourselves in certain activities that we could demonstrate to the children and have them participate in, but it’s different when you’re actually interacting with the children,” she says. “Sometimes one activity doesn’t work, and that’s okay. A big part of it is improvising and finding what works for the specific child you’re with.”

Ten children enrolled for the six-week season, and attendance at each practice varied depending on summer schedules. “The parents really appreciated the opportunity,” Vanessa says. “It was a chance for them to bring their kids and relax, that they were accepted for who they were.”

Carly, mother to seven-year-old Nora, says that her daughter loved the program. “She had the shin guards and the big socks and the jersey, and she was super into it. She loved it on the days she got to wear it to daycare because I’d pick her up and we’d run to soccer right after. She just thought it was the best thing in the world. She has a soccer ball at home here now.”

Carly can also attest that the program created a safe space not only for her daughter, but for her as well. “It’s nice when you’re with all the other Down syndrome parents,” Carly says, “So that when my kid is throwing a tantrum, I don’t feel like I have to explain myself. If you’re with people who aren’t familiar with Down syndrome, they don’t mean to treat you differently, they just walk a bit more on eggshells, so it’s kind of nice when we have our own group.”

While the youth participants were honing their soccer skills throughout the season, the teen teachers were learning too.

If there’s one thing that Vanessa believes the teen teachers got out of the program, it’s that it gave them an opportunity to see that kids with disabilities are just kids at the end of the day. “They had an opportunity to work with kids without disabilities in other programs,” Vanessa shares, “and they said there really were a lot of similarities between the kids: they all have attention problems, they all had engagement problems.”

“I feel as though there is a huge societal generalization placed on persons with disabilities, especially children,” says Haleema. “You think, ‘how may I accommodate to their needs?’ Of course, different children will have different needs that you’ll have to accommodate, but coming out of it, you’ll realize that these children are children. Their disability doesn’t make them any less capable or willing to participate in an activity.

“Not only did the experience improve my abilities to work with children,” Haleema continues, “but it shifted my reality…Biggest of all, I learned that until you get that experience with any person with a disability, never assume that they are any less capable than a person without.”

The teen teachers have enjoyed themselves so much that they are asking about other volunteer opportunities to work with children with disabilities. In addition, the parents love that their children can work at their own pace and weren’t forced into a competitive soccer environment. “It was nice doing it with our group and not feeling pressured if [Nora] didn’t want to do something or didn’t understand how to do something,” Carly shares.

Given the success of this program, Vanessa is now asking herself what’s next, but she recognizes that there isn’t a one-size fits all model if she were to expand the program to children with varying disabilities, whether those be cognitive or physical.

“We geared this toward one disability and so things would look different if you had multiple, different disabilities or if you were gearing it toward kids with autism or physical disabilities,” she explains.

As Vanessa continues to work through her doctorate program and to help design inclusive programming, initial lessons learned during the summer program will undoubtedly play a significant role.